CRITICAL MYSTERY STUDIES PRIMER

Department of Chicana/o Studies

By Matthew David Goodwin

CMS is the critical and interdisciplinary study of mysteries such as ghost hauntings, alien encounters, and monster sightings, among many more. We examine the role of mystery in the long traditions, histories of resistance, and cultural expressions of BIPOC communities, and at the same time, we explore how mysteries are entangled with racism, sexism, coloniality, and other systems of oppression. Studies within CMS explore the nature and meaning of mysteries, the discourses surrounding them in their specific geographical and cultural contexts, their fictional representation in fiction and film, and how mysteries have been reclaimed, reinterpreted, and reappropriated by BIPOC cultural creators.

Elements of a Mystery

A mystery in our way of using the term is a problem/question that has not been solved/answered, and that resists understanding. It is a subset of the larger and generic category of the “unknown.”

Mysteries need time to form (repeatedly not being solved) and often have the air of the ancient about them (if not, a legendary status must be invented).

We are typically looking in particular at mysteries with an element of the fantastic or the extraordinary. This is consistent with the etymology of the term “Mystery” (that it is connected to the supernatural).

Mysteries are inherently about us and them (because there are people who know and those who don’t, and because they bring our differing beliefs about the fantastic out into the open).

Mysteries are always somewhere and must be considered in their historical/cultural context.

Mysteries draw us in, and we must react (zero objectivity). {This scares the Academy and accounts in part for why this class has not existed before}

Mysteries are good stories because of the importance of ambiguity and inviting gaps to storytelling, and so become entertainment {also suspect in the Academy}.

Escenarios:

Even though mysteries have this questioning at its heart, mysteries cannot be reduced to such questions.

Mysteries are always a scenario, that is, a amalgamation of questions, culture, politics, history, and performance

Mysteries as scenarios help us see that mysteries are not there to be solved by us, rather it points to the many directions and connections for study.

The Crux:

The primary tension that CMS points towards can be found in its etymology. We typically mean mystery to refer to something unknown, strange, and that in fact resists being known or understood completely. At the same time, the etymology points towards a different perspective. In the mystery rites of ancient Greece, mustḗrion is “a secret rite”, and mústēs is the “initiated one” which comes from muéō, “I initiate” and múō, “I shut”. And so, the original meaning had to do with having the secret knowledge, rather than not having it, and that it is information that is known but is kept secret (so much so that if an initiate told others about the secret rites of the Eleusinian mysteries they would be killed. This worked so well that we do not actually know them). So this not only points to the relativity of the Mystery (for one person, the chupacabras is a mystery for another it is something real that happened to their abuela) but also to the spiritual and ethical element that some things called mysteries by outsiders can be an important secret ritual to an insider, especially as regards to the relationship between indigenous groups worldwide and colonizers (who initially wanted to destroy the rites, then through academia to discover and understand them).

But in both instances, the repeatedly unknown and the secret ritual, we can call them a mystery, as the term has those two meanings historically and etymologically. The intention of CMS is to outline the Crux of the field rather than to normalize it.

Evolution of a Mystery (not always linear)

Context

The Foundational Mystery (swirling empty space that we are always one step away from)

Reaction of the local community, media, world

Reframing (the multiplication of mysteries)

Mystery Hunters

Commercialization, Tourism

Artistic depictions and CMS Study

Entanglement (direct, indirect, forced)

Entanglement as we are using it refers to the deep connection that a mystery has to systems of oppression. For example, Roswell and colonization.

Entanglement is not just a random product of joining a mystery and historical memory or oppressive systems. It happens for a reason. The two sides benefit each other:

--The habitual system of oppression helps to make sense of the mystery because it is fantastic and difficult to understand.

--The mystery helps to keep alive the colonial narrative (or racist or sexist)

Paul Edward Montgomery Ramírez: “This connection of Mothman to disaster entangles it with the ‘Indian curse’ settler myth”.

There are pitfalls with the Entanglement Theory as with any theory: for example, misunderstanding entanglement as a single allegory (Roswell is the story of colonization punto, whereas in fact a number of systems of oppression enter the Roswell mystery).

Resonance

“This chapter, then, continues to describe and perform a vernacular poetics. I focus here not on the shape, history, or limits of the genre, but rather on the resonance that emerges as people create parallels between various stories and images, and as they use those parallels to theorize power. It emerges in moments of American metadiscourse about what people often call the weird stuff in the world: the inexplicable, the uncanny, the apophenias that point to a pattern and structure lying beneath the surface of things.”

Susan Lepselter, Evidence of Things Unseen

Trace Reactivation

“[t]he traces of indigenous savagery and “Indianness” . . . stand a priori prior to theorizations of origin, history, freedom, constraint, and difference. These traces of “Indianness” are vitally important to understanding how power and domination have been articulated and practiced by empire, and yet because they are traces, they have often remained deactivated as a point of critical inquiry as theory has transited across disciplines and schools.”

Jodi A. Byrd, The Transit of Empire

Lo real maravilloso:

“The presence and vitality of this marvelous real was not the unique privilege of Haiti but the heritage of all of America, where we have not yet begun to establish an inventory of our cosmogonies. The marvelous real is found at every stage in the lives of men who inscribed dates in the history of the continent and who left the names that we still carry: from those who searched for the fountain of eternal youth and the golden city of Manoa to certain early rebels or modern heroes of mythological fame from our wars of independence.”

Alejo Carpentier, Prologue to The Kingdom of this World (estatica milagrosa)

Academic Authenticity:

If we write our own experience, write it authentically:

“I was eight pages through a shitty third draft when I finally gave in. My writing wasn’t genuine. I was trying to make my “essay about the New Mexico homeland” an essay about someone else’s “New Mexico homeland.” (Kelly Medina-López)

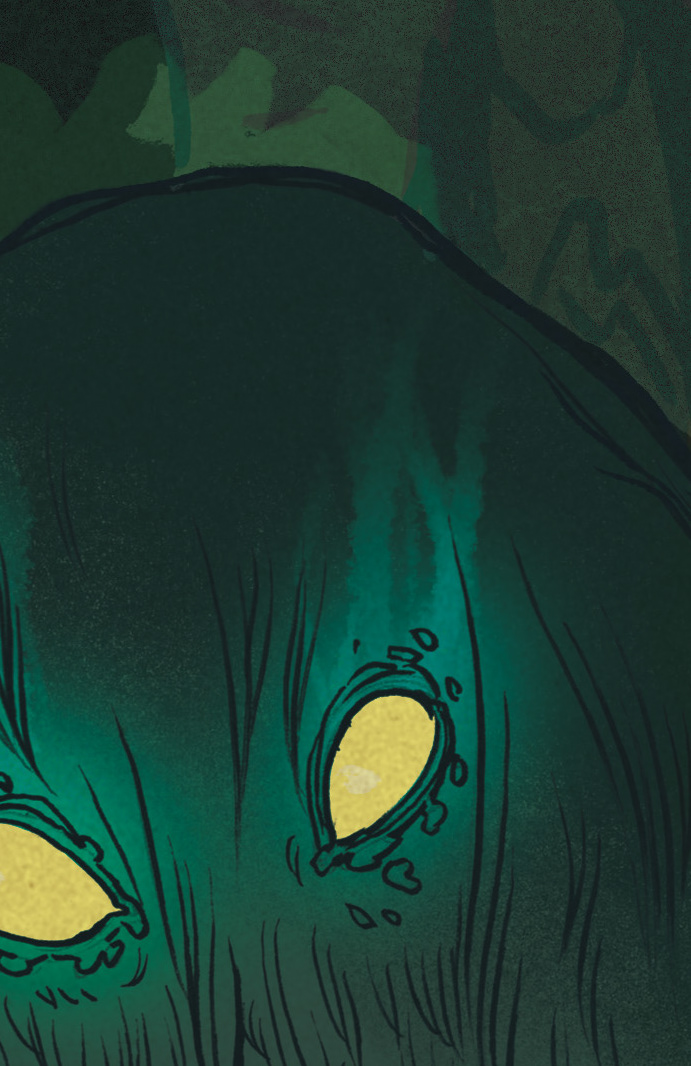

Aesthetics of Mysteries and the Mysterious

Absence and invisibility

Desire

Time-worn, old, grainy photo/video

Wink, sly smiles or Opacity

The X

Fog, Shadow

Narrative (determine if the focus is on the seeker or the sought after)

CMS Research Methods

Textual Analysis

Visual Analysis

Historical Research

Critical Theory and Cultural Studies

Field Work

Ethnography

Autoethnography

Qualitative/quantitative research

“Monster Culture (Seven Theses)” Jeffrey Jerome Cohen

Thesis 1: The Monster’s Body Is a Cultural Body

Thesis II: The Monster Always Escapes

Thesis III: The Monster Is the Harbinger of Category Crisis

Thesis IV: The Monster Dwells at the Gates of Difference

Thesis V: The Monster Polices the orders of the Possible

Thesis VI: Fear of the Monster is Really a Kind of Desire

Thesis VIII: The Monster Stands at the Threshold... of Becoming